Mon Dec 29 16:04:20 2025

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| NVIDIA-SMI 580.105.07 Driver Version: 581.80 CUDA Version: 13.0 |

+-----------------------------------------+------------------------+----------------------+

| GPU Name Persistence-M | Bus-Id Disp.A | Volatile Uncorr. ECC |

| Fan Temp Perf Pwr:Usage/Cap | Memory-Usage | GPU-Util Compute M. |

| | | MIG M. |

|=========================================+========================+======================|

| 0 NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2050 On | 00000000:01:00.0 Off | N/A |

| N/A 52C P0 8W / 30W | 0MiB / 4096MiB | 0% Default |

| | | N/A |

+-----------------------------------------+------------------------+----------------------+

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| Processes: |

| GPU GI CI PID Type Process name GPU Memory |

| ID ID Usage |

|=========================================================================================|

| No running processes found |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+tiny GPT

In this post, I will implement a tiny version of the GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) model using PyTorch. This implementation will cover the essential components of the GPT architecture, including tokenization, embedding layers, transformer blocks, and the training loop. I will keep adding to the blog, so stay tuned for updates!

Setting the Environment

I start by installing CUDA inside Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL)1 and then installing PyTorch with CUDA support2. Once I’ve installed the CUDA toolkit and PyTorch, I verify the CUDA version and PyTorch access to CUDA using the following command:

1 For instructions on installing CUDA in WSL, see the NVIDIA documentation.

2 For instructions on installing PyTorch with CUDA support, see the PyTorch installation guide.

2.9.1+cu130

TrueI have CUDA version 13.0 and PyTorch 2.9.1+cu130 installed. I start by importing the necessary libraries to the notebook:

Preparing the Dataset

I will work with a dataset of BBC news articles [1]. My goal is to train a tiny GPT model to generate news articles similar to those in the dataset, given an arbitrary title. Let’s start with downloading the dataset and unpacking it:

# !mkdir -p datasets

# !wget http://mlg.ucd.ie/files/datasets/bbc-fulltext.zip -O datasets/bbc-fulltext.zip -nv

# !unzip -q datasets/bbc-fulltext.zip -d datasets/

# !rm datasets/bbc-fulltext.zip

# !wget http://mlg.ucd.ie/files/datasets/bbcsport-fulltext.zip -O datasets/bbcsport-fulltext.zip -nv

# !unzip -q datasets/bbcsport-fulltext.zip -d datasets/

# !rm datasets/bbcsport-fulltext.zipI have downloaded two datasets: one with 2225 BBC News articles and 737 BBC Sports articles from 2004-2005. Now, I will combine all the text files into a json single file, with a list of articles. I use multiprocessing to speed up the process as there are many files to read:

def process_file(file_path):

with open(file_path, 'r', encoding='utf-8') as f:

article = f.read()

return article

# Check if dataset exists

assert (os.path.exists('datasets/bbc') and os.path.exists('datasets/bbcsport')), "Dataset not found! Please download the dataset first"

# Get all files in the dataset directory

file_list = []

for root, dirs, files in os.walk('datasets'):

for file in files:

if file.startswith('README') or file.endswith('.json'): # skip README files, and existing json files

continue

else:

file_list.append(os.path.join(root, file))

# Read and process files in parallel

pool = mp.Pool(processes=os.cpu_count()-4) # I have 16 CPU cores, here I am using 12 cores

jobs = pool.map_async(process_file, file_list)

pool.close()

pool.join()

# Collect results and save in a single json file

dataset = jobs.get()

json.dump(dataset, open('datasets/dataset.json', 'w'))Before I proceed, let’s take a look at a sample article from the dataset, as shown below:

Here is the first article from the dataset of 2962:

Looks and music to drive mobiles

Mobile phones are still enjoying a boom time in sales, according to research from technology analysts Gartner.

More than 674 million mobiles were sold last year globally, said the report, the highest total sold to date. The figure was 30% more than in 2003 and surpassed even the most optimistic predictions, Gartner said. Good design and the look of a mobile, as well as new services such as music downloads, could go some way to pushing up sales in 2005, said analysts. Although people were still looking for better replacement phones, there was evidence, according to Gartner, that some markets were seeing a slow-down in replacement sales.

"All the markets grew apart from Japan which shows that replacement sales are continuing in western Europe," mobile analyst Carolina Milanesi told the BBC News website. "Japan is where north America and western European markets can be in a couple of years' time. "They already have TV, music, ringtones, cameras, and all that we can think of on mobiles, so people have stopped buying replacement phones."

But there could be a slight slowdown in sales in European and US markets too, according to Gartner, as people wait to see what comes next in mobile technology. This means mobile companies have to think carefully about what they are offering in new models so that people see a compelling reason to upgrade, said Gartner. Third generation mobiles (3G) with the ability to handle large amounts of data transfer, like video, could drive people into upgrading their phones, but Ms Milanesi said it was difficult to say how quickly that would happen. "At the end of the day, people have cameras and colour screens on mobiles and for the majority of people out there who don't really care about technology the speed of data to a phone is not critical." Nor would the rush to produce two or three megapixel camera phones be a reason for mobile owners to upgrade on its own. The majority of camera phone models are not at the stage where they can compete with digital cameras which also have flashes and zooms.

More likely to drive sales in 2005 would be the attention to design and aesthetics, as well as music services. The Motorola Razr V3 phone was typical of the attention to design that would be more commonplace in 2005, she added. This was not a "women's thing", she said, but a desire from men and women to have a gadget that is a form of self-expression too. It was not just about how the phone functioned, but about what it said about its owner. "Western Europe has always been a market which is quite attentive to design," said Ms Milanesi.

"People are after something that is nice-looking, and together with that, there is the entertainment side. "This year music will have a part to play in this." The market for full-track music downloads was worth just $20 million (£10.5 million) in 2004, but is set to be worth $1.8 billion (£9.4 million) by 2009, according to Jupiter Research. Sony Ericsson just released its Walkman branded mobile phone, the W800, which combines a digital music player with up to 30 hours' battery life, and a two megapixel camera. In July last year, Motorola and Apple announced a version of iTunes online music downloading service would be released which would be compatible with Motorola mobile phones. Apple said the new iTunes music player would become Motorola's standard music application for its music phones. But the challenge will be balancing storage capacity with battery life if mobile music hopes to compete with digital music players like the iPod. Ms Milanesi said more models would likely be released in the coming year with hard drives. But they would be more likely to compete with the smaller capacity music players that have around four gigabyte storage capacity, which would not put too much strain on battery life.

Notice that here I have a list of articles, each containing a title, a summary line and the corresponding text. Each article is a list of words, spaces, and newline characters (e.g., \n). To train our tiny GPT model, I need to represent this text data in for of numbers. The easiest way to do this is through building a look-up table that maps each unique item of text to a unique integer. This process is called tokenization.

Tokenization

At the lowest level, the articles are a string of characters. These characters join together to make words, and words join together to make sentences, and so on. With character-level tokenisation, I represent each unique character (e.g., ‘a’, ‘b’, ‘c’, …,‘!’,‘?’, etc.) with a unique integer. The model will then learn to generate text one character at a time. This gives a smaller number of unique tokens to represent (i.e., the vocabulary size). However, since I am generating text one character at a time, the sequence of characters required to make a sentence will be longer. Alternatively, if I use a word-level tokenization, where each unique word is represented by a unique integer. This would give us a larger vocabulary size but a shorter sequence length. Let’s break this down further with an example. Below I show the first 10 items in a character-level and word-level tokenization:

first_article = dataset[0]

print(f"\nThe first article has {len(set(first_article.split()))} words, and {len(set(first_article))} characters.")

char_tokens = list(first_article)

print(f"\nThe first 10 character tokens are: \n{char_tokens[:10]}")

word_tokens = first_article.split()

print(f"\nThe first 10 word tokens are: \n{word_tokens[:10]}")

The first article has 326 words, and 65 characters.

The first 10 character tokens are:

['L', 'o', 'o', 'k', 's', ' ', 'a', 'n', 'd', ' ']

The first 10 word tokens are:

['Looks', 'and', 'music', 'to', 'drive', 'mobiles', 'Mobile', 'phones', 'are', 'still']The work-level tokenisation present much more information with just 10 items compared to the character-level tokenisation. Hence, there is a trade-off between vocabulary size and sequence length when choosing between level of tokenisation used in natural language processing (NLP). For better performance, the commercial GPT models use sub-word tokenisation, which is a hybrid approach that balances vocabulary size and sequence length 3. It combines the word with the preceding spaces as a single token, as shown below:

3 For more information on sub-word tokenization, see the Tokenizer from OpenAI.

For simplicity, I will start with a character-level tokenisation for this tiny GPT model. I will add two special tokens to the vocabulary: <startoftext> and <endoftext>, which indicate the start and end of an article, respectively. These tokens help the model understand where an article begins and ends during training and generation. Let’s build the character-level tokenizer:

# Combine all articles

data = []

for article in dataset:

data.append("<startoftext>") # Add start token before each article

data.extend(list(article)) # Extend the data list with characters from each article

data.append("<endoftext>") # Add end token after each article

# This is redundant, since any character that is not the data will not be trained on. I add this on make sure the model can handle all these characters at inference stage.

characters = [

'<startoftext>', '<endoftext>', '\n', ' ', '.', ',', '!', '?', "'", '"', ';', ':', '-', '(', ')', '[', ']', '{', '}',

'0', '1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '6', '7', '8', '9',

'a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h', 'i', 'j', 'k', 'l', 'm', 'n', 'o', 'p', 'q', 'r', 's', 't', 'u', 'v', 'w', 'x', 'y', 'z',

'A', 'B', 'C', 'D', 'E', 'F', 'G', 'H', 'I', 'J', 'K', 'L', 'M', 'N', 'O', 'P', 'Q', 'R', 'S', 'T', 'U', 'V', 'W', 'X', 'Y', 'Z'

]

# Create vocabulary

vocab = list(set(characters).union(set(data))) # List of unique characters

print(f'Vocab size: {len(vocab)}') # Print vocabulary size and the vocabulary list

# Average characters per article

print(f'Total number of characters in the dataset: {len(data)}')

avg_chars_per_article = len(data) / len(dataset)

print(f'Average number of characters per article: {avg_chars_per_article:.0f}')Vocab size: 92

Total number of characters in the dataset: 6494404

Average number of characters per article: 2193I have 92 unique characters in total, including letters, digits, punctuation marks, spaces, and newline characters. Each article has an average of 2193 characters. This is an important metric to consider when deciding on the sequence length of text for training the model.

Next, I create a mapping from characters to integers and from integers to characters. These mapping processes are known as encoding and decoding, respectively. Here, I define two functions, encode and decode, to perform these mappings:

# Encoding and decoding functions

def encode(text, vocab):

char2idx = {ch: idx for idx, ch in enumerate(vocab)}

return [char2idx[ch] for ch in text]

def decode(indices, vocab):

idx2char = {idx: ch for idx, ch in enumerate(vocab)}

return ''.join([idx2char[idx] for idx in indices])

# Test encoding and decoding

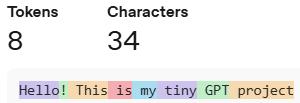

encoded = encode("Hello! This is my tiny GPT project", vocab)

print(f'Encoded: {encoded}')

decoded = decode(encoded, vocab)

print(f'Decoded: {decoded}')

# Encode the entire dataset

tokens = encode(data, vocab)Encoded: [59, 35, 91, 91, 18, 52, 53, 26, 86, 57, 44, 53, 57, 44, 53, 82, 42, 53, 43, 57, 49, 42, 53, 64, 40, 26, 53, 56, 41, 18, 39, 35, 79, 43]

Decoded: Hello! This is my tiny GPT projectEmbedding

Now, I have the articles represented as sequence of integers where each integer corresponds to a unique character in the vocabulary. To make predictions about the next character in the sequence, I want to represent the characters in a continuous domain. Additionally, I want to be able to make some associations between the characters. This could be like associating uppercase letters with lowercase letters, or associating punctuation marks with spaces. Essentially, I want have a way to bringing together characters that have similar context. This is done by representing each character as a vector in a continuous, high-dimensional space. This process is known as embedding, and the vector of each character is updated during training. This process allows the model to learn relationships between characters based on their context in the training data, thereby, bringing similar characters closer together in the embedding space4.

4 For a visual illustration, I recommend this video by 3Blue1Brown on how word vectors encode meaning.

5 For more information on PyTorch’s Embedding layer, see the official documentation.

Here, I define an embedding layer using PyTorch’s nn.Embedding class5. The embedding layer takes the vocabulary size and the desired embedding dimension as inputs. The output of the embedding layer is a tensor of shape (batch_size, sequence_length, embedding_dim), where each character in the input sequence is represented by its corresponding embedding vector.

# Define embedding layer

num_embeddings = len(vocab)

embedding_dim = 16

Embedding = torch.nn.Embedding(num_embeddings=num_embeddings, embedding_dim=embedding_dim, device=device)

# Test embedding layer

sample_text = ["Hello", "World"]

sample_tokens = list(encode(item, vocab) for item in sample_text)

sample_tokens_tensor = torch.tensor(sample_tokens, dtype=torch.long, device=device)

sample_embedding = Embedding(sample_tokens_tensor)

print(f'Sample text: {sample_text}')

print(f'Sample indices: {sample_tokens}')

print(f'Sample embedding shape: {sample_embedding.shape}')Sample text: ['Hello', 'World']

Sample indices: [[59, 35, 91, 91, 18], [29, 18, 41, 91, 71]]

Sample embedding shape: torch.Size([2, 5, 16])In the sample test above, I have 2 sequences, each with 5 characters. As each character is represented as a 16 dimensional vector in the embeddings, I have the embedding tensor of shape (2, 5, 16). Here, I defined the value of embedding_dim as 16 and num_embeddings as the vocab_size, which is determined by the tokenization (which is 92 in this case). I did not define the sequence length or the batch size - they were inferred from the input tensor shape. To train the model, I need to fix the sequence length, as this will affect the architecture of the model. Batch size can vary during training, depending on the available memory - as it is used as way of utilizing the GPU memory efficiently.

P.S. To be continued…